The Limits Of Charity

Thursday 15th of September 2005

If Sydney and its Jewish community is a bit Los Angeles, then Melbourne Jewry is the closest thing we have to pre-war Warsaw.

Some 40,000 Melbourne Jews manifest every passionate Jewish position between them. The Adass has a strong presence, but then so does Habonim. The Bundist school, Bialik, teaches Yiddish, and the Lubavitch have an iron grip on orthodox life. (Several shuls have been forced to adopt Lubavitch liturgy when they’ve appointed Lubavitch rabbis, for example, and a unit in the Jewish Studies A Level equivalent is “a study of Chabad”.)

Some renegade orthodox have established a Shira Hadasha shul imitating the radical feminist/egalitarian orthodox prototype Shira Hadasha in Jerusalem.

A huge proportion of young Jews attend Jewish day schools. The 2,000-strong Mount Scopus is a bit JFS-like, while Yeshiva High is more Hasmo. London doesn’t yet have an equivalent to King David, Melbourne’s Progressive Jewish school (about 850 pupils), nor anything quite like the 1,000 strong Bialik. Beis Rivka is the Lubavitch girls’ school which, together with its counterpart boys’ school, accommodates nearly 1,000 children from across the orthodox range. And so on.

They have only one kashrut authority, but every shul is independent and does its own thing. Melbourne’s LimmudOz last year attracted 850 people to its first ever two-day fest of learning Limmud-style and they figure it can only grow. One of the commercial cinemas is to run regular films of Jewish and Israeli interest all through the year because they reckon there’s a viable market. There’s even an eruv which everyone seems to use.

On my visit there last weekend, I was invited, amongst other speaking engagements, to deliver a d’var Torah to the Shabbat afternoon gathering of the Mizrachi shul, a right-of-centre-but-Zionist community whose members take their Judaism sufficiently seriously that the Shabbat afternoon congregation numbered at least 100. I addressed the Jewish principles underpinning Tzedek, the Third World development charity I chair.

When I’d finished, several people thanked me for this “breath of fresh air” or “challenge to our parochialism”. Some said it was helpful to be forced to think about our place in the wider world. And then an astonishing thing happened. When we went back into shul for ma’ariv, the rabbi went into the pulpit and proceeded to try to dismantle all I’d said – very politely but very firmly. He must have spoken for 15 minutes, stressing, for example, that the need to follow justice referred only to justice between Jews. He concluded by accepting that Jews should be an example, but that that was best done by looking after “our own” in an exemplary manner. Others then would be impressed and would look after “‘their own” too. If this were to happen, then there’d be no need for Jews to give to such charities as I had described.

Several people told me afterwards how strongly they disagreed with him, but clearly what he’d said was music to the ears of others.

But I have three questions. How can a learned Jew, especially just before Yom Kippur, when we read about Jonah being forced to prophesy to Nineveh, talk such claptrap about Jews only looking after their own? And, in the wake of, for example, the London bombings, how do we know who is “our own” and who is excluded? And, finally, when all of his congregation buy cheap clothes from the Far East, coffee from Latin America and chocolate from Africa, how does he decide that he’s not inextricably linked with the global community?

But don’t get me wrong. This could have been London as easily as Melbourne. You don’t have to live in a small community to have a small mind, nor live miles away to be far distant from thoughtful understanding.

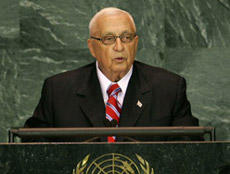

The photo is not from his talk in Melbourne. I think what Clive has said about Melbourne is spot on. Living in such a tolerant and Jewish-friendly society as we do, I has always bothered me that support for non Jewish causes, particularly the terrible genocide occurring in Darfur, is not given enough attention.